|

| Home |

the

Vierings |the Vogts

Ernst

Krenek | von Trapp family

Hubertus Prinz zu

Löwenstein-Wertheim-Freudenberg

More Americans claim German descent than from any other ethnic group. Of those millions of Germans who emigrated to "Amerika" in the first third of the 20th century, the rise of National Socialism in the land of their birth complicated their lives. While family and friends remained in the Old World, their growing familial ties and adopted communities in the New one vied for their complete loyalty. In the case of the Vierings, Fritz would confront his family over what he assumed to be an imminent war between Germany and its many enemies. The Vogts would befriend some of those Teutonic warriors caught up in the subsequent global conflagration in their Iowa farm home. Click on the links to learn more about their experiences. |

|

|

||||

Fritz and Augusta Viering Natives of rural Hessen, in Central Germany, the Vierings created flourishing new lives for themselves in Iowa yet found themselves in conflict with family and Nazi-convert friends back in a Germany trapped in Hitler's trance. Like their neighbors the Vogts, the Vierings used German-POW labor on their farm to take in important war-time harvests. After the war, the Vierings sent innumerable Care Packages to their village, helping friends and family survive the post-war crisis. |

Herman

and Martha Vogt

Martha Vogt left her native Schleswig-Holstein for Iowa in 1909. Her husband Herman a German POW in France during WWI came to Iowa in 1921. During the Second World War, this immigrant couple used German-POW labor on their farm and, in the process, struck friendships with men from their homeland that would last half a century. |

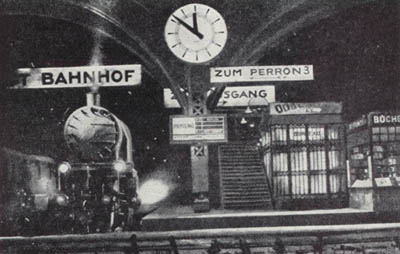

German and Austrian Exiles Many German and Austrian newcomers to "Amerika" in the early 20th century came voluntarily, but some did not. Political, intellectual or artistic dissidents were not welcome in the Neues Deutschland, the "New Germany" (which included annexed Austria), and found a safe haven in the New World, including the Midwest. Unexpectedly, they included princes and musicians, as the following articles attest: 1900-1991 Born in Vienna in 1900, composer Ernst Krenek achieved popular success with the jazz-inflected opera Jonny spielt auf (Johnny Strikes Up the Band). Ernst and his wife, actress Berta Haas, fled Europe in 1938, with assistance from violinist Louis Krasner, who later became concert master of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. First assuming teaching positions in Boston and then at VassarCollege, Ernst subsequently came to Hamline University in Saint Paul, where he served as head of the music department from 1942 to 1947. He took American citizenship in 1945 and in 1947 moved to Los Angeles. Kreneks music was included in the Nazis Entartete Musik (degenerate music) exhibit in Duesseldorf in 1938. The Nazis applied the scientific term degenerate to a wide range of music atonal, jazz and, especially, works by Jewish composers. Though Ernst Krenek was Roman Catholic, Jonny spielt aufs lead character was a black jazz fiddler, the composer worked with atonal and serialist forms, and he was associated with the Jewish composer/conductor Gustav Mahler. (Ernst had been briefly married to Mahlers daughter, Anna, a painter and sculptress, and he was engaged to complete Mahlers unfinished 10th Symphony by the composers widow, Alma Mahler Gropius.) While at Hamline Krenek composed a number of works reflecting the tragedy of war, including Lamentatio Jeremiae prophetae, op. 93, and Cantata for Wartime, op. 95. The latter used a text from Herman Melville and was scored for female voices due to the lack of male singers at Hamline during wartime. (The information about Ernst Krenek was supplied by the Schubert Club of Saint Paul/Minnesota.) |

|

|

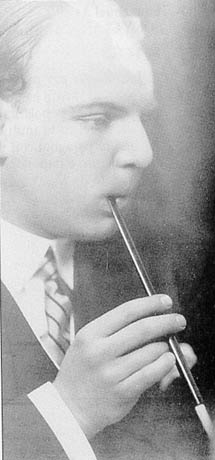

| Ernst Krenek as a young man in Vienna, circa 1920 | |

|

|

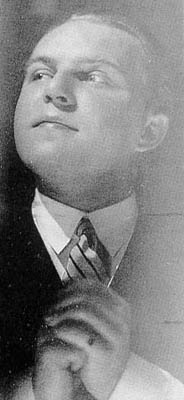

a scene from Krenek's musical Jonny spielt auf at

the Wiener Staatsoper (Vienna State Opera) |

|

|

|

Nazi poster decrying Krenek's musical Jonny spielt

auf |

a "Degenerate Music" poster from the Nazis |

|

|

Ernst Krenek teaching, circa 1940s | top | |

|

the real von Trapp Family |

the von Trapps as portrayed in The Sound of Music |

|||||

Does the world meet in Iowa? Is it really the unacknowledged Center of the Universe? It might seem so, at times, when the apparently least-probable scenarios become everyday.

the von Trapp Family Singers' tour bus in America

Around the time of the von Trapps' visit, another Teutonic guest at the hostel, Hans Frey, made two sketches of Scattergood, below:

Sources:

sketches: Robert Berquist photos: Your Sound of Music Keepsake. (Colordruck, Salzburg: Colorama, 2008), pages 22, 53 and 18, respectively. |

||||||

| top |

|

|

It was the greatest migration in Western musical history to one concentrated area, in one period, for one reason. These four (Otto Klemperer, Prinz Hubertus von Lowenstein, Arnold Schoenberg and Ernst Toch) may never have socialized in Europe, but that all changed in the intimate and isolated emigre musical world of Los Angeles. (Photo: Yale University Press) A Perfect Storm: Hitler, Hollywood and the Great Emigre Musicians |

|---|

In January 1941, he decided to settle down in Newfoundland, near New York, to make a home for their daughter. He started teaching at Rudges University near Newfoundland. After the Pearl Harbour attack on 7 December 1941 Hubertus Prince zu Löwenstein started teaching at different universities again.

He arrived in the beginning of October 1942 in St. Paul, Minnesota. This is the only university he discusses in his autobiography. This joyful time and especially his friendship with John W. Larson, which he would treasure for the rest of his life, made this university stay special to him.

In his own words, he recalled, “A few days after the christening I left for Hamline University, in St. Paul, Minnesota, where I was to offer a course of twelve lectures on Europe, Past and present. But during the six weeks at that time-honoured and very good school, I finally held no less than forty scheduled lectures, not counting a lot of unscheduled ones, informal meetings, seminars, and so forth. The work load of a college teacher in America is far heavier than in Europe- and when one came from Europe and was supposed to know almost everything, it was still heavier.’

‘The battle of Stalingrad had just started when I came to Hamline. A world historic decision will have been reached by the time I leave, I said in my first lecture.” [xvi]

The "Prinz" only visited for some six weeks, yet this exotic guest's sojourn at Hamline University would leave a decades-long, indelible wake. By coincidence a guest lecturer at the same institution where Austrian-exile and composer Ernst Krenek found an adopted home, Hubertus used his time in exile both to educate his "hosts" about events taking place in Nazi-occupied Germany, but also to inform his own evolving worldview. He would use the new perspectives gained while safely out of Hitler's reach, in the heart of the American Heartland, to guide him in post-war Germany, as he and like-minded colleagues struggled to form a new nation out of the ruins of Nazi rule.

In 1943 he discovered that through writing short stories for newspapers he had a chance to reach people who skip the political pages of a newspaper. He tried to hide the political message behind funny and interesting plots. They dealt with Germany and the Nazis and were actually appreciated by the readers.

The Prinz wrote of his next visit, “In May 1943 I returned to Hamline University to receive the honorary degree of Doctor of letters. In replying to the citation, I said that I looked upon this honour as intended also for those German universities from whom in the years of freedom I had received my academic training…straight from the academic celebration I went on a canoe trip on the wild and beautiful St. Croix River, together with Hans Christian Larson. [xvii] He describes that experience as reminiscent of his childhood and his dreams about journeys through Germany and Italy after the war. During the trip they both were able, for a time, to forget about the war.

The Prinz wrote the following report about some of the highlights of his time at Hamline University:

|

|---|

Postwar GermanyIn December 1945, seven months after the Nazi Reich was defeated, Hubertus asked for permission to re-enter Germany, but this was turned down by the Soviets, since they regarded him as a nationalist whose views clashed with communism. On September 20, 1946 he finally was able to return to Germany, arriving in October. Löwenstein had always desired to return as early as possible,

[xviii]

but he stated in his autobiography that the 12 years of statelessness were a real and an integral part of his life, one he did not regret.

[xix]

He was granted his dormant citizenship back from the senate of Bremen on November 29th. Later that year, the family Löwenstein moved to Bad Godesberg, near the new West German capital of Bonn.

[xxi]

In 1947, he founded Deutsche Aktion, (German Action) a movement with the aim to shape a new democratic German government. That year he also taught for the University of Heidelberg in the summer term. Tragically, the faculty conspired to get rid of him, because they disliked his anti-Nazi lectures. They tried to convince the American military government that his lectures were actually strongly nationalist.

[xxii]

In 1948, his friend Larson from Minnesota, who was now a student of the University of Heidelberg, came to visit him. On March 3, 1949, he once more had a private audience with pope Pius XIII. The Pope found himself forced to admit that Löwenstein had been right the first time they had met, and that he should have listened to Hubertus’ warning. Pope John XXIII decorated Hubertus Prince zu Löwenstein for his work to reconcile the Roman Catholic and the Greek Orthodox Church. In November that year he got one step further toward his goal of a general election under United Nation auspices. This was the Heidelberg Resolution. In December 1950, the Helgoland Affair came to a head. Helgoland was a German island, which the English intended to bomb in order to destroy it completely. They disliked the idea of a German island so close to England itself. On 27 December, Löwenstein and the Minnesotan Larson went to Helgoland. They planned a peaceful occupation of the island to prevent it from being destroyed. Two students from Heidelberg came along. To find a boat which would take them out to the island from Cuxhafen was more than difficult. They took the lighthouse, which was the best preserved building on the island, as their shelter. They brought a radio with them to be able to follow the news. Of course, the press got wind of their plan and actually one day before they left for the island the newspapers reported that they were on Helgoland already. The British army was not overwhelming impressed by that and admitted that they would have continued their bombing if not the American Larson would have been there. Getting the Americans involved was too risky for them. A few days after their arrival, reporters arrived as well as others who also wanted to protect the island. Not long after Larson left the island, a British marine boat left for Helgoland. On board were German policemen as well as British soldiers. Löwenstein negotiated with the British and negotiated a settlement in which the island would remain German territory and untouched by the British. He and his followers left the island on the British ship. In July 1951, Hubertus became involved once more in a political adventure. He now advocated for the Saar to remain German territory. Again he was arrested in the Saarbrücken, for holding illegal open air meetings. A second time, his friend Larson saved him by informing the press in Marburg Germany, which lead to Löwenstein’s discharge. In October 1955, a referendum defined that the Saar was and remained a German state. In 1952, Hubertus moved to Munich after being hired as editor for the southern German newspaper, Die Zeit. That year he also finished his book Streseman: The German Destiny in the Mirror of His Life. Writing this book was very important to him, as well as meeting with Stresemann’s family, whom he had previously met in exile. From 1953 till 1957, Löwenstein was a member of the German parliament. He was there as a member of the liberal FDP (Free Democratic Party). He was on the committees of Foreign Affairs, All German Questions, and Berlin and Youth affairs. In 1957 he left this party and instead joined the DP (German Party), because he disagreed with the FDP’s voting against joining NATO in 1956. In October 1957, following his career as a member of parliament, he got involved in what was probably his most dangerous political adventure. He left for Budapest following a successful revolution by the Hungarians against the Soviets. He wanted to strengthen the ties between the German government and the new Hungarian leaders. Unfortunately the Soviets acted against him in November and now Larson’s warning phone call from Wiesbaden was too late. Löwenstein and Zühlsdorff were arrested when they tried to flee. Löwenstein’s diplomatic passport was taken away and given back when he was finally set free with the help of the French embassy. This embassy, the only one still existing in Budapest, managed to bring Löwenstein, Zühlsdorff and many other people of different nationalities out of the country, which was now at war with Russia. In December that year he and Zühlsdorff decided to write a book about NATO. They visited Greece for their research, which was enduring a civil war at this time, the USA, and Asia. Konrad Adenauer agreed to write the introduction to their book.

an article about the Prinz in Manchester Guardian Weekly, vol. 98, no. 15, 11 April 11 1968 From 1958 till 1973 Hubertus functioned as a special advisor on international affairs for the German government. He continuously travelled the world to lecture, study and interpret in order to support the new government. In 1973 he also became the head of the Free German Authors Association. His guiding idea in the post war times was that of a United Europe, with national self-reliance and cultural preservation, but also a united market. On his class reunion in 1965 he felt like an outsider among his former classmates who all had clearly-defined positions. [xxiii] He felt like leaving again when materialism was ruling democracy and when Neo-Nazis showed up, but as long as he was able to fight these powers in Germany he stayed. [xxiv] He believed in the youth and knew that the new generation was not responsible for what the older one did. [xxv]According to The New York Times, Hubertus died on 28 November 1984 at the age of 78, suffering from peritonitis.

[xxvi]

|

[i]

Prince Hubertus zu Löwenstein, Towards The

Further Shore,

London 1968 p. 164

[ii]

Löwenstein, Towards The Further Shore, p.19

[iii] Ebenda, p. 108

[iv]

ebenda p.70

[v]

ebenda p. 80-81

[vi]

Scotland on Sunday

[vii]

Löwenstein, Towards The Further Shore, p.85

[viii] Volkmar Zühlsdorff, In Begleitung Meiner Zeit. Essays- Erinnerungen- Dokumente, Munich 1998, p.168

[ix]

Löwenstein, Towards The Further

Shore, p.88

[x]

Zühlsdorff, In Begleitung meiner Zeit,

p.169/170, Löwenstein Towards The Further Shore, p.

105

[xi]

Zühlsdorff, In Begleitung Meiner Zeit, p.

170

[xii]

Scotland Sunday

[xiii]

Löwenstein, Towards the Further Shore, p. 126

[xiv]

Scotland

[xv]

Zühlsdorff, p.170

[xvi]

Löwenstein, Towards The Further

Shore, p. 256

[xvii]

Ebenda, p. 261

[xviii] Ebenda, p. 11

[xix]

Ebenda, p.9

[xx]

Löwenstein, Towards The Further Shore, p. 11

[xxi]

times

[xxii]

Löwenstein, Towards The Further

Shore, p.317

[xxiii]

Löwenstein, Towards The Further Shore, p. 46

[xxiv] Ebenda, p.12 [xxv] Ebenda, p. 405

[xxvi]

times

[xxvii] Zühlsdorff, p.166 |