| Home |

| Home | |

Postmarked

from Amsterdam As World War II loomed over Europe, an innovative Iowa educator was bringing the situation home to her students. One spring day in 1940 the seventh- and eight-grade teacher at the Danville Community School in Des Moines County offered her students the chance to correspond with pen pals overseas. One of her students, Juanita Wagner, drew the name of a ten year-old girl in the Netherlands—Anne Frank. The name “Anne Frank” resonates for us today because of the diary of the young Jewish girl kept while in hiding from the Nazis during World War II. First published nearly fifty years ago, the diary is the story of an ordinary teenage girl facing extraordinary circumstances. She details in her diary the usual adolescent fears about growing up, falling in love and being misunderstood by her parents. Yet she also writes as a Jew hiding from the Nazis as the war raged outside. Readers of the diary all over the world have come to see her as a heroine of the war because, in spite of all she suffered, she still felt that people were inherently “good at heart.” Her words have touched generations of people who continue to struggle to understand the complexities of a world war in human terms. Few realize, however, that long before The Diary of a Young Girl became legendary, a few pages of Anne Frank’s thoughts came to Danville, Iowa, in the spring of 1940. This brief connection between Amsterdam and Danville was because of the work of Birdie Mathews to bring those worlds together. By 1940, Mathews was a veteran teacher. She had been teaching since age eighteen having begun her career at nearby Plank Road rural school, where she taught grades Kindergarten through eighth until she was past forty. About 1921, she moved to the Danville Community School, having spent over two decades at a country school, where she had taught a wide range of curriculum and varying ages and levels of students. No doubt this had made her a seasoned teacher. But, Mathews had accumulated other experiences as well, overcoming the professional isolation that plagued particularly rural and small town teachers. These teachers had few opportunities to interact with colleagues outside of their buildings. Even help from the Iowa State Department of Education seemed distant; only local administrators could make request for its limited materials. In an effort to bring new teaching practices and ideas to rural teachers, the State University of Iowa and other colleges brought traveling workshops, called Tri-County Institutes, to regional locations each fall. Similar to today’s in-service days, the institutes met for a half- or whole-day session of speakers and workshops. The institutes minimized the isolation of rural teachers and furthered their professional growth. Birdie Mathews most likely participated in some of these sessions, since they were often required of all staff. Yet she also spent summers studying at Iowa State Teachers College in Cedar Falls and Colorado State University, as well as Columbia University in New York, where according to her diary, she took three courses—“Education and Nationalism,” “Modern Trends in Classroom Practices” and “Character an Personality Testing.” Few teachers had the time, resources or incentive for this level of professional education. “Miss Birdie,” as her students called her, acquired more teaching resources through travel. She was even a bit of a local celebrity when she sent home lengthy letters to the Danville Enterprise detailing her 1914 trip to Europe. Her letters became front-page news, and her travel experiences became classroom lesson plans. Her students remember fondly the afternoons when they would gather around Mathews to hear her adventures. Opening their eyes to the world beyond, she frequently sent postcards to her students from her travels overseas and across the country, and it is believed that on one of these trips she acquired the names of potential pen pals for her students. Because pen-pal writing as a class room practice was still fairly rare at this time, only creative teachers such as Birdie Mathews would have set up situations in which their students cold learn firsthand about the world. Some Danville students wrote to other children in the United States, but many, including Juanita Wagner, chose to write to overseas pen pals. In her introductory letter in the spring of 1940, Juanita, age ten, wrote about Iowa, her mother (a teacher), sister Betty Ann, and life on their farm and in near by Danville. She sealed the letter and sent it to Anne Frank’s address in Amsterdam.

In a few weeks Juanita received not one, but two overseas letters. Anne had written back to Juanita, and Anne’s sister Margot, age fourteen had written a letter to Betty Ann, Juanita’s fourteen-year old sister. “It was such a special joy as a child too have the experience of receiving a letter from overseas from a foreign country and a new pen pal,” Betty Ann Wagner later recalled. “In those days we had no TV, little radio, and maybe a newspaper once or twice a week. Living on a farm with so little communication could be very dull except for all the good books from the library. The Frank sister’s letters from Amsterdam were dated April 27th and the 29th and were written in ink on light blue stationary. Anne and Margot had enclosed their school pictures. The letters were in English, but experts believe that the Frank sisters probably first composed their letters in Dutch and then copied them over in English after their father, Otto Frank, translated them. In her letter Anne told of her family, her Montessori school, and Amsterdam. She must have pulled out a map of the United States because she wrote. “On the map I looked again and found the name Burlington.” Enclosing a postcard of Amsterdam, she mentioned her hobby of “picture-card collecting: I have already about 800.”

Anne made no mention of the political situation in Europe. Her sister, Margot, however, wrote Betty Ann that “we often listen to the radio as times are very exciting, having a frontier with Germany and being a small country we never feel safe.” Referring to their cousins in Switzerland, Margot remarked “We have to travel through Germany which we can not do or through Belgium and France and in that we cannot do either. It is war and no visas are given. “Needless to say we were both thrilled to have established communications with a foreign friend, and we both wrote again immediately,” Betty Ann recalls years later. The Wagner sisters anxiously awaited a second reply postmarked “Amsterdam.” But, no reply came. Although they did not know that the Frank family was Jewish and therefore in grave danger as the Third Reich advanced, Betty Ann did consider that mail might be restricted or censored. Wondering what had happened to their new Dutch pen pals, the Wagner sisters waited. Anne’s April 29th letter to Juanita had been written just three weeks after Germany had invaded Denmark and Norway—that spring had proved to be a successful one for the Nazi campaign in northern Europe. On May 10, eleven days after Anne wrote her letter, the Dutch surrendered to the Nazis.

At first, little seemed changed in the Netherlands except for the presences of soldiers on the streets. Yet Jews slowly began to feel the effects of the Third Reich. By October 1940 Otto Frank as a Jew would be required to register his business. By June 1941, when Anne Frank would be turning twelve, Jews would be forced to carry identity cards stamped with the letter “J.” In the fall of 1941 Ann and Margot, like other Jewish children in Holland, would have to attend a separate school.

Europe’s volatile situation seemed far removed from the world of Juanita and Betty Ann Wagner, where students thought of the war in Europe as they thought of ancient history, that is, as hardly relevant. Yet gradually, the war became more of a reality for the Wagner sisters, their teacher Birdie Mathews and other southeastern Iowans. Scattered articles about the war in Europe began to appear in the Burlington Hawkeye Gazette and Des Moines County News. In 1940, a war munitions plant was built between Danville and nearby Middletown. The munitions plant was somewhat controversial: on the one hand it brought new jobs to the local economy; on the other, it took almost a dozen family farms in the area. Temporary housing was constructed for people moving to the area for the jobs. Draft notices began arriving. On Fridays, “Current Events Day,” students in Birdie Mathews class and other classrooms discussed articles and radio broadcast about the war in Europe. Suddenly, in December 1941, the bombing of Pearl Harbor catapulted the United-States—and Danville, Iowa—into the war. Worried that something had happened to Anne and Margot, Betty Ann and Juanita Wagner still waited for a reply as winter dragged on. No letters came.

By the spring of 1942, in Anne and Margot Frank’s world across the Atlantic, Jews were now forced to wear yellow Star of David on al of their clothing and were forbidden to use public transport. Soon many other restrictions came. Anne would write in her diary: “Jews must hand in their bicycles… must be indoors from eight o’clock in the evening until six o’clock in the morning; Jews are forbidden to visit theaters, cinemas and other places of entrainment.” Anne was just entering adolescence, and such restrictions surely affected her budding social life. Later she would record in her diary her friend’s comment that “you’re scared to do anything because it may be forbidden.

When the Frank family received an arrest notice for Margot, they were scared enough to go into hiding on July 6,1942. Otto Frank planted clues around their apartment to suggest the family had fled to Switzerland. Their hiding place was the rear part of the building where Otto Frank had his business in the heart of Amsterdam. Thee door to the “Secret Annex,” as Anne called it, was hidden behind a bookcase in one of the offices. A business acquaintance, Herman van Pels and his wife and son, Peter, also joined them. A few months later a Jewish dentist, Fritz Pfeffer, also moved into the annex (making a total of eight people hiding in four small rooms and a water closet). Four of Otto Franks coworkers knew about the annex above their offices; they supplied the families with food and news of the outside world. Although her letter writing to Danville had long since ended, Anne wrote faithfully in her diary.

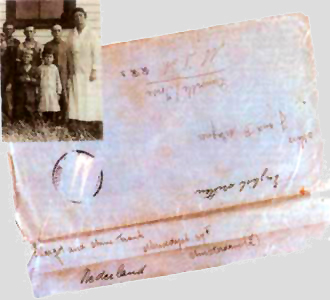

Ten-year-old Anne Frank writes to Juanita Wagner in Iowa: Experts

believe this is the only surviving letter written by Anne Frank in English.

On August 4, 1944, while Danville residents were reading about the Polish underground and the Nazis’ flight from Florence in the Burlington Hawkeye Gazette, German police entered the secret annex and arrested the Frank and van Pels families and Fritz Pfeffer. Within a month they were transported by train with many other Dutch to Auschwitz, a death camp in Poland. The men and women were separated, but Anne and Margot were allowed to stay with their mother until October 1944, when the sisters were transferred to Bergen-Belsen. Their mother died in January 1945. At Bergen-Belsen conditions were atrocious, food was scarce and thousands were dying from disease. Anne discovered an old school friend in another section of the camp; the two girls talked through the barbed wire separating them. As winter ended, typhus swept through the camp. Margot became ill first and died in March 1945. A few days later, just weeks before the British liberated the camp, sixteen-year-old Anne died. After the war was over, Betty Ann Wagner was teaching in a country school in eastern Illinois. Still curious about the Dutch pen pals, she wrote again to Anne’s address in Amsterdam. A few months later she received a long, handwritten letter from Otto Frank. He told about the family hiding, of Anne’s experiences in the “secret annex” and how Anne had died in a concentration camp. This was the first time Wagner learned that Anne had been Jewish: “When I received the letter I shed tears” Wagner recalled, “ and the next day took it with me to school and read Otto Frank’s letter to my students. I wanted them to realize how fortunate they were to be in America during World War II.” By 1956 Wagner had settled in California and was driving home from work one day when she heard a review on the radio of a Broadway play called The Diary of Anne Frank. Thinking it might be the same Anne Frank, she rushed to ordered a copy of the play. As soon as it arrived she realized it was indeed her sisters pen pal: a photo similar to the one from Anne appeared on the cover. Although Otto Frank’s letter had been misplaced during one of the Wagner family’s frequent moves, Betty Ann had carefully kept Anne and Margot’s letters safe. In the late 1980’s the letter became part of the collections of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, where they are now on display. And what of Birdie Mathews, the small town teacher who by a combination of innovative teaching and pure chance briefly connected the Wagner sisters and the Frank sisters? “Miss Birdie” had retired the year the war ended, having built a local reputation as a devoted teacher who never hesitated to create special opportunities for her students. Years earlier she had started what she considered the county’s first drivers’ education program: during recess, she taught farm boys to drive her car. The trade-off was that now that they knew how to drive and could borrow Mathew’s car, they had to keep coming to school despite seasonal demands of farm work. When the Great Depression hit in the 1930’s, Mathews had refused her salary so that fuel could be brought to keep the school heated and open. She often organized class picnics and wiener roasts at a park or her home. One former student recalled when “Miss Birdie” took her to a state spelling contest and an overnight stay at the University of Iowa—a truly exciting trip for a youngster from Danville, population 309 in 1940. Because Danville was a small community and Mathews came from a large family, she taught many of her nieces and nephews; they often remarked that she was tougher on them than on the other pupils in an effort to avoid favoritism. Although revered by her students, she was known as a strong disciplinarian. One former student recalled her response to a particularly obnoxious boy; “Miss Birdie took him in the hallway and shook him until his shirt buttons popped off.” After her retirement in 1945 Mathews’s sense of exacting detail and organization translated easily into her long-time love of needlework and gardening. A meticulous gardener, she believed that “flowers do something for a person—brightens up a home.” Every year she shared her abundant vegetable crops with friends and relatives, and she continued to volunteer at the Danville Congregational Church, where she and her family had deep roots. She remained involved in the lives of her many nieces and nephews. With more time to travel, she took several trips to sunny locations during long Iowa winters. She had always kept travel diaries. Now retired, she took more care to keep day-to-day dairies current. As the years progressed Mathews traveled less, yet she continued an active correspondence with friends and former students. She died in 1974, at age ninety-four. Today, Betty Ann and Juanita Wagner continue to tell their story about their brief connection to Margot and Anne Frank, aware that even the most ordinary person can be a part of extraordinary situations. Against a backdrop of an approaching world war, three human impulses briefly connected: Miss Birdie Mathews’s vision to broaden her students world view; Juanita Wagner’s desire for an overseas pen pal, and Anne Frank’s eagerness to respond as “your Dutch friend,” as she signed her letter. As a result, a few letters were exchanged and a few friendships sprouted one spring a half-century ago, when Amsterdam came postmarked to Iowa. In early July 1942, when Anne’s family decided to go in to hiding, Anne wrote in her diary about packing hurriedly: “ The first thing I put in was this diary, then hair curlers, handkerchiefs, schoolbooks, a comb, old letters; I put in the craziest things with the idea that we were going into hiding, but I’m not sorry, memories mean more to me then dress.” Could some of the old letters she packed have been postmarked “Danville, Iowa”? Thirteen-year-old Margot Frank writes to Betty Ann Wagner:

While sightseeing in Washington D.C. in August 1941, Birdie Mathews wrote in her travel diary that she had seen the Magna Carta, “which has been sent here from England for safe keeping during the bombing.” In Amsterdam, far closer to the bombing, Anne Frank had not even begun her diary yet. She would receive it as a birthday gift from her father the next June. Frank’s diary would be short but intense and emotionally honest. Mathew’s diary would be at first kept sporadically (during her travels), but then almost daily as she detailed her life in Danville, Iowa, as a retired teacher. Each diarist wrote about what was important to her. Each diary—as all diaries do—gives a unique view of the world. Yet Anne Frank's diary that became known around the world was not exactly the same diary in which Anne first wrote. There are actually three versions. She began her cloth-bound diary on her thirteenth birthday, June 12 1942. She wrote about the war (the families in hiding, listening to the wireless daily) and her everyday experiences with her in the secret annex. She wrote mostly for herself, using the diary as a place where she could be alone and express her feelings. On March 28,1944 Anne heard a radio broadcast requesting letters and diaries detailing individual wartime experiences. She began to consider writing her experiences as a book, calling it het Achterhuis (“the house behind” or “secret annex”). That May she began earnestly to rework her original diary for publication, recopying her entries onto loose-leaf paper, and adding and editing selections, changing the names of some of the people in the annex. She edited her entries through March 29, 1944. At the time of her arrest on August 4, 1944, Anne’s original diary and her revisions were left behind. Otto Frank’s co-worker Miep Gies gathered them up to save for Anne. When Anne’s death was confirmed, Gies gave them to Otto, who had not read his daughter’s diary before this. Otto Frank soon began to translate excerpts into German to send to his mother in Switzerland. At first he translated portions for family and friends only, but after excerpts were shared with the publishing community, the diary soon became a work for a larger audience. A publisher worked closely with Otto Frank in editing the diary, selecting largely from his excerpts. (Otto did not wish passages about Anne’s difficulties with her mother and certain intimate entries to appear.) This version was published in the Netherlands in 1947 and in the United States in 1952. All three versions of the diary now appear together in The Diary of Ann Frank: The Critical Edition (1989). An unabridged version of the 1952 diary was also published. Birdie Mathews, the teacher who arranged the pen pal exchange for Anne Frank and Juanita Wagner, also was devoted diarist. Her diaries, recently donated to the State Historical Society in Iowa by Vivian and Don Kellar (Birdie Mathews’ grand nephew) begin with travel diaries kept during her frequent trips and her post retirement winters in Florida and California. Each entry was carefully handwritten on loose-leaf paper or plain typing paper, or in composition books or unused teacher record books. Once retired, Mathews devoted even more time to her diaries, writing nearly everyday until her death at age ninety-four in 1974. She detailed her everyday activities and daily regimens with great care. For example, an entry from October 15, 1967, reads “Rainy all day. The chili supper scheduled for tomorrow night called off on account of flu epidemic.” In an entry from February 22,1952 she wrote “Washington’s 228th birthday. Cold. The Gerdes boys came with their snow plow and shovel and clean the snow from my walks. Paid them $1.25.” At times her topics expanded to world events. On July 19,1950, the eve of the Korean War, she noted “Listened to President Truman’s message tonight, sounds exactly like Dec, 1941. Must we go through all that again? God forbid.”

Mathews seldom recorded deeply personal perspectives, although some of her earlier travel diaries include a few poems and reflections on her travels. Although lacking the emotional impact or historical significance of Anne Frank’s adolescent diary kept while hiding from the Nazis, the Birdie Mathews diaries give us a glimpse into the orderly life of a rural Iowa teacher who tried to broaden her students and community’s world view by sharing her experiences. The portrait that emerges from Mathews diaries is of a career schoolteacher who organized her life as she did her diary pages-with clarity and detail. “Iowans are fortunate to have discovered the story of Birdie Mathews, as it serves as a strong reminder of the role Iowans can play in world affairs,” remarked Mary Bennett, audiovisual archivist at the State Historical Society of Iowa (Iowa City), where the Mathews Diaries are now housed. “Rather then remain complacent and uninvolved this school teacher took and active interest in events across the globe. She encouraged her students to look outside of their relatively secure lives in Iowa in order to gain insights about the turmoil faced by people like Anne Frank. Her diaries and writings are significant because they document her worldly attitude and the experiences she gained while traveling abroad. It is fortuitous that her family preserved these research materials for future generations, so we can gain a new perspective on how World War II impacted IowanThis article is reprinted from the Palimpsest (winter 1995) and used by permission from the State Historical Society of Iowa. | Home | |