|

Vernon W. Tott was born and raised in Iowa, across the river from South Dakota.

Although he is not a South Dakota veteran, his proximity, his

recollections, and his photographs make his story a special addition to

this book. And, as Vernon says, "I am a fisherman and I think I

fished every lake and river in your state many times." What better

qualification to become an honorary South Dakotan for this publication?

Service Record: Corporal Vernon W. Tott served as a radio operator for the 84th

Division "Railsplitters" and had seen 180 consecutive days of

action, including the major battles of Rhineland-Central Europe and the

Ardennes, "Battle of the Bulge." The 84th Division had 1438

killed in action and 5098 wounded in action, most of which were in the

Battle of the Bulge. 70,000 German POWs were captured by the 84th

Division. The weather was cold and there was much snow; the riflemen in

the infantry divisions slept on the cold ground in deep snow and rain.

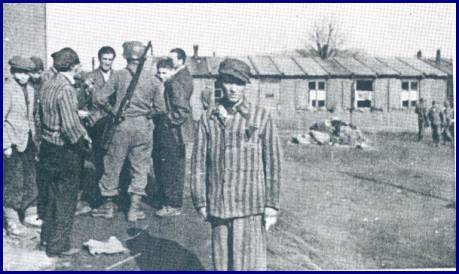

On April 10, 1945, the 335th Infantry Regiment of the 84th Division, came

upon Hannover-Ahlem, a slave labor camp primarily made up of men and boys

from the liquidated Lodz Ghetto in Poland. A subcamp of Neuengamme,

Hannover-Ahlem was created for the purpose of using Jews as slave labor to

dig tunnels underground and build an underground factory that the American

Air Force couldn't bomb.

Camp Encounter: The following is Vernon's recollection of events, told in his own

words.

I was a radio operator in the Infantry and on April 10, 1945, we

were going to attack Hanover, Germany. Early that morning I was sitting in

my radio jeep with Capt. Reed, at a crossroad, west of Hannover. After the

sun came up we could see down a dirt road that someone was waving to us.

Capt. Reed thought these people might be American POW's so he told me to

drive down to them. A couple truckloads of riflemen came with us. When we

got there we could see that it was a Jewish slave labor camp (Ahlem). What

we saw inside of the camp was Hell on Earth.

My memory of what we saw when we first entered the camp was the

pile of dead bodies. The men alive were in ragged clothing and they were

just skin and bones. They came towards us with smiles on their faces. They

knew their horrible nightmare was finally coming to an end.

We motioned them back as we didn't want them to get too close to

us. We feared they were full of disease and lice. We threw cigarettes and

food rations that we had on the ground in front of them. We could see they

were starving for food. Capt. Reed used my radio to call division

headquarters and told them what we had come across and to send us some

help.

Then we went into one of the barracks. What we saw in there is

something that a person could never forget. There were prisoners laying in

bunks too weak to get up. There were dead bodies in some of the bunks. In

one particular bunk, there was a boy, about fifteen years old, who was

lying in his own vomit, urine, and stool. I could see he was near death.

When he looked at me, I could see he was crying for help. Over the years,

every time I would think about Ahlem, I could still see the look on this

boy's face.

Next, I went into another barracks and it was just as bad as the

first one. There was a prisoner there that could speak English. He told me

he was a doctor from Belgium, and said that this was the infirmary. He

explained that he was the camp doctor. The prisoners here, I could see,

were near death. He had no medicines or bandages to help treat the

prisoners. Then he took me to look out the back window. There were

trashcans full of dead bodies. All skin and bones. What a horrible,

inhuman way to die! Our troop had just come through six months of bloody

battle but what we were seeing here made us sick to our stomachs and some

even cried.

Our next building was the kitchen. There were two large steam pots

where the food was cooked. This camp had five buildings with an

electrified fence around it. There was no running water and in the middle

of the camp was a trench. It was unbelievable. The prisoners were expected

to straddle it to use as their toilet. The prisoners had diarrhea and no

toilet paper was available. This had to be a very humiliating experience

for these prisoners. The smell was horrendous.

What I saw in this camp was so shocking that I wanted pictures to

send home to show my family. I took eighteen photos of everyone that was

alive in the camp. In the Army, we had no radios or newspapers so I didn't

know Hitler was treating the Jewish people in this manner. After the war

these photos laid in a shoebox, in my basement, for fifty years.

In addition to Hannover-Ahlem, Vernon's division also liberated a

camp in Salzwedel, Germany, where there were 2700 Jewish women [and some

300 non-Jewish women]. Across the highway from the Salzwedel camp were the

Adolph Hitler barracks at a German airfield. General Bolling had us burn

the camp down and we moved all these prisoners into these modern barracks.

Capt. Charles E. Wilson is quoted as saying, "Those people were

starving. After we set up our messes, they fought to get in line. Under

the German system, thirty people were given food for ten and the ten who

fought the hardest stayed alive. We told them that there was enough for

all and that they could have seconds if they wanted. They wouldn't believe

it. After a while, they began to settle down."

Awards: Combat Infantryman Badge

|