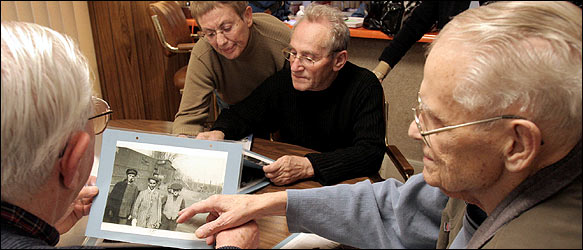

Mark Kegans for The New York Times

Vernon Tott,

right, was with the 84th Infantry Division in April 1945 at the

liberation of Ahlem, a Nazi labor camp in Germany. Two survivors

of the camp, Henry Shery, left, and Lucjan Barr, with his wife,

Ruth, looked at Mr. Tott's photos from Ahlem at his Sioux City,

Iowa, home last week.

By JODI WILGOREN

Published: February 20, 2005

SIOUX CITY, Iowa, Feb. 19 - The two old men stared into a 60-year-old

snapshot, searching for the truth that tied them together across

time.

"This face I remember," Lucjan Barr, 76, said of the sullen, scared

teenager. "I don't know to who it belongs, but I remember. It could

be me."

A minute passed, the men talked of the past, then Vernon Tott,

80, picked up the picture again. "That's you there," he said, hope

breeding confidence. "I can see by the way your ear is shaped. To

me, that could be you."

Mr. Barr, an electrical engineer in Tel Aviv, survived the Holocaust

at the tiny Ahlem labor camp near Hannover, Germany. Mr. Tott, a

retired meatpacking foreman here in Sioux City, was an Army radio

operator who pulled out his vest-pocket camera to document the horror

he saw while helping liberate Ahlem.

Their reunion here on Thursday capped Mr. Tott's decade-long quest

to find the few dozen men in the 19 photographs he took that day

and compile their stories into an inch-thick homemade book. With

Mr. Barr and Henry Shery of Manchester, N.J., who joined the picture

party here, Mr. Tott has located 30 Ahlem survivors, 13 of whom

have found their faces in his frames.

After forgetting about the pictures, stored in a shoebox in his

basement, for half a century, Mr. Tott has traveled to Germany and

Poland in recent years on his search for survivors. He was scheduled

to go to Israel this summer and to be honored in May at the United

States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, but the cancer in

his stomach now prevents him from traveling. So the survivors came

here to present Mr. Tott with a silver kiddush cup at a candle-lighting

ceremony on Friday at a local synagogue.

"You brought us back to the human race," Mr. Shery, a retired medical

supply salesman who learned about Mr. Tott only 10 days before,

said as they held hands.

What makes this Holocaust story stand out is the photographs, stark

black-and-whites showing the frightened, famished faces of the few

who survived months of forced labor at Ahlem and were too weak to

join the death march the Germans had ordered days before liberation.

The pictures, online at www.jou.ufl.edu/documentary/prod/Ahlem/album,

show piles of dead bodies waiting to be burned. There are living

skeletons slurping thin soup. Boys in too-big wool caps and coats

dropped off by the Red Cross. Men scratching lice from their heads

in front of the infirmary, which Mr. Barr recalled as "a one-way

street: you walk in and don't walk out."

For the survivors, the pictures are the proof to illustrate the

stories they struggle to share with grandchildren. For Mr. Tott,

they are a symbol of his service, a way to bear witness. For historians,

they are rare artifacts of a little-known labor camp, and an unusual

opportunity to complete a circle between victims and saviors.

"There are plenty of photographs of the concentration camps," said

Churchill Roberts, director of the Documentary Institute at the

University of Florida, who is making a film, titled "Angel of Ahlem,"

about Mr. Tott. "There are not many where you can pair the photograph

with the actual person today. The power of this photograph, to see

yourself, 50 or 60 years later, and the flood of memories it brings

back, it's really quite something for us just to watch."

Mr. Tott, whose great-grandfather, coincidentally, was born in

Hannover, bought a Kodak pocket camera for a dollar at a New Orleans

pawn shop while training with the 84th Infantry Division in 1942.

He pulled it out whenever he saw a bombed-out bridge or an airplane

aflame, sending the film home to his mother. In the hour he spent

at Ahlem on April 10, 1945, he shot two rolls.

Fifty years later, Mr. Tott was reading The Railsplitter, the 84th

Infantry's newsletter, in his fading recliner in his small ranch

home here, when he came upon a letter from Benjamin Sieradzki, a

retired engineer in Berkeley, Calif., wondering about the young,

tall, blond soldier with the camera.

"I always remembered him; he was clicking away by himself, I thought

it was very unusual," Mr. Sieradzki, now 78, recalled in a telephone

interview. "In a way, I needed them," he said of the pictures. "I

needed to have some kind of legitimacy to what I was telling people

about what happened there."

Mr. Sieradzki is the young man on the far left in picture

No. 9, the one with the pile of bodies in the background. When

Mr. Tott first sent him copies of the pictures, he blew them up

big as could be to see the sorrow in his eyes. Now, he keeps them

in a drawer. But barely a week passes that he does not speak with

Mr. Tott; in the documentary, they walk arm in arm through a field

that once was the labor camp.

"That's a horrible way we met, Ben," Mr. Tott says,

"but now we're good friends."

A few years ago, the survivors sent Mr. Tott a new Pentax camera.

One man, a shoe salesman, sends four or five pairs every year

to Mr. Tott and his wife, Betty. Another, Jack Tramiel, the founder

of Commodore computers, gave $100,000 to the Holocaust museum

in Washington in Mr. Tott's name.

The pictures were included in a German textbook published last

year about Ahlem, which housed about 1,000 Jewish prisoners from

the Lodz ghetto in Poland, most of whom did not survive the war.

And Mr. Tott has made some 400 photocopies of his own archive,

a ragtag mix of survivors' memoirs, handwritten letters, German

newspaper articles and other memorabilia, for survivors' families,

students and his neighbors.

Lina McMillan, one of perhaps 300 Jews in Sioux City - counting

babies, people in nursing homes, and students away at college

- came to the service Friday to thank Mr. Tott on behalf of herself,

her son and her daughter. "I know had it not been for people

like Vernon Tott, we wouldn't be here," said Ms. McMillan,

48, whose father, Abraham Izbicki, survived five years in Auschwitz.

The night before, Mr. Barr and Mr. Shery flanked Mr. Tott at

his Formica table, stories spilling out as they searched for themselves

in the photographs. "One skeleton looked like the other,"

Mr. Shery said.

Mr. Barr told of his first night of freedom, having to sleep

on the floor because the bed was too soft. Mr. Tott remembered

tossing cigarettes and food rations to men who had nothing. Mr.

Shery recalled being beaten while working in the mines.

Mr. Barr picked up a particularly horrific image, of a man barely

more than bones lying in a bunk, then pushed it away in disgust.

He paused at another, showing four young men crowded into the

triple-bunks.

"You know him?" Mr. Tott asked.

"I believe it is me," Mr. Barr said quietly.

In the end, neither man who made the pilgrimage to Mr. Tott's

home in what his family thinks may be his finals days recognized

himself in the photos. The scared teenager in that first photo

was still in his prison uniform, and Mr. Barr remembers changing

into civilian clothes the Red Cross brought. The one lying in

the triple-bunk could not be him, he said, "because I was

on the move."

But "it's the same as if it was me," Mr. Barr said.

"I was one of the guys he made believe he was a human being."

| Home |

|