|

| Home |

the village of

Kuelte in Hessen, Germany; the Kuelter Burg ("Castle") can be

seen on the hill, in the background

“Do

you think I want to live with holes in my pants for the rest of my life?”

The Viering Family’s German-Immigrant Story

as told by Meta Viering Lage; edited by Michael Luick-Thrams

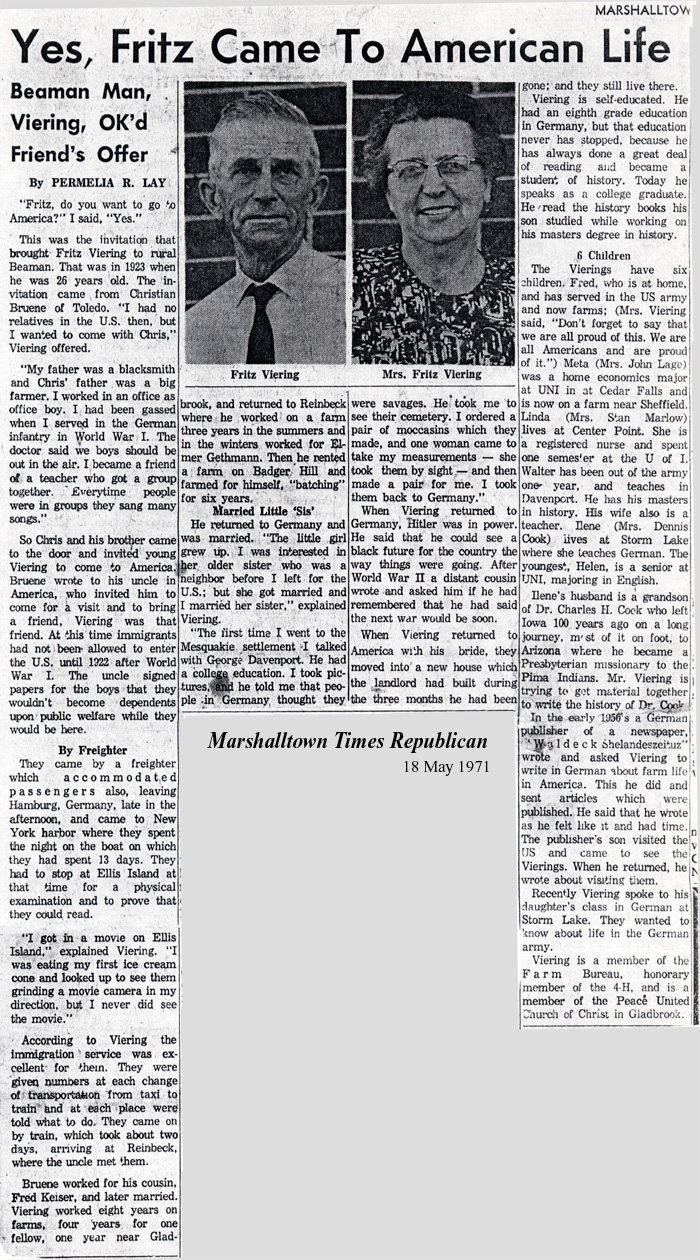

My father, Fritz Viering,

was born and reared in an agricultural community in Hessen, in Central

Germany. He was 17 years old when World War I broke out in Europe in 1914.

His father was the village blacksmith and the family owned a very small

farm on the Kuelte Berg [a big hill]. As a youngster, he sometimes stayed

out all night to watch soldiers practicing military maneuvers. Dad’s

mother had died of tuberculosis in 1909, when he was eleven years old.

His father died on the 16th of February, 1921—two years before Fritz

came to America.

In 1997 and 1998, as we Viering children

were going through our parents’ things, we found a narrative that

Dad had written of how he came to “Amerika”. He recorded

his recollections because he realized

Alzheimer’s was making it increasingly difficult for him to remember.

Dad’s narrative was probably written in the late 1970s. He began

to write in English and later switched to German, evidently because it

must have been easier for him.

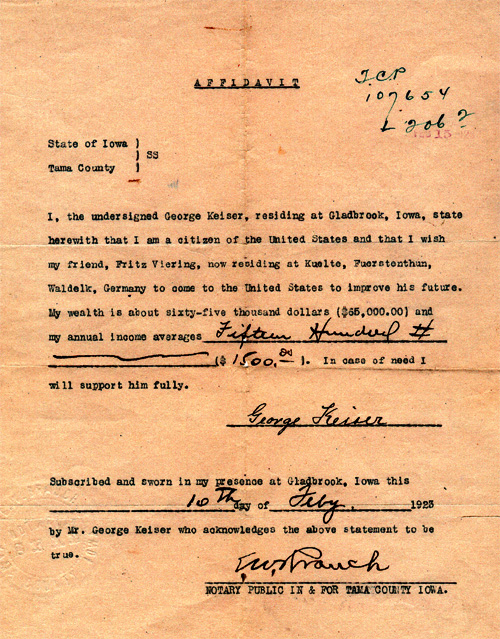

Dad came to America in April 1923. (He

had served in WWI and there are newspapers accounts that tell of those

experiences.) A German named Georg Keiser, who farmed east of Gladbrook,

Iowa, sent a letter to his nephew, Christian Bruene, and said to him “Come

to America”. Chris had planned to come with another friend, a certain

Herr Obermann. Obermann decided to stay in Germany, however, because his

girlfriend was pregnant. Tickets were changed from “Obermann”

to “Viering”.

In the narrative my father related, “It

was then that Christian Bruene found me at the Wachenfeld Haus on Kuelter

Hackenberg, where I was with my friend, Ludwig Naeser. Christian Bruene

entered with his brother and said ‘Fritz, do you want to go along

to America’. I said ‘Ja’ [‘Yes’]”.

This story was told to us children many times. We always thrilled in its

telling.

In later years, we learned that Dad’s family had tried to talk him

out of going to America. On one occasion, as related by a cousin, he looked

down at his pants, full of holes, and said “Do you think I want

to live with holes in my pants for the rest of my life?” They sailed

on the S.S. Bayern for America, ready for adventure.

In later years, we learned that Dad’s family had tried to talk him

out of going to America. On one occasion, as related by a cousin, he looked

down at his pants, full of holes, and said “Do you think I want

to live with holes in my pants for the rest of my life?” They sailed

on the S.S. Bayern for America, ready for adventure.

Fritz and Chris entered Ellis Island on

the 8th of April 1923. My father called it the “Island of Tears”.

While most immigrants passed through in a few hours, the possibility of

rejection struck terror in the hearts of the immigrants. He saw a bribe

take place as someone with a withered hand slipped an inspector some cash.

“As immigrants carried their luggage up the great stairway to the

Registry Room, they underwent—without their knowing it—a six-second

medical exam. Doctors at the top of the stairs watched for lameness and

shortness of breath. Doctors also checked for signs of a highly contagious

eye disease called trachoma”. Dad had his first ice cream cone on

Ellis Island, and he said that as he was eating his cone, he turned and

observed a cameraman filming him for a newsreel.

(Years

ago I once gave a lesson about Ellis Island and interviewed my mother

about what she knew. My mother told of a friend who never spoke much of

her Ellis Island experiences because she came as a 15-year-old girl, alone

with her younger brother. They were detained at Ellis Island for a week

because there was a question about their sponsorship. They had to stay

while they wrote for a letter to be sent to relatives and to receive the

reply, guaranteeing that they had financial backing and would not become

wards of the state. The girl remembered an overweight matron with a tattered

apron, with a huge ring of keys, who showed them to sleeping facilities.

Mom also mentioned Gus Wrage, a Gladbrook friend, who was one of twins

born on Ellis Island.) (Years

ago I once gave a lesson about Ellis Island and interviewed my mother

about what she knew. My mother told of a friend who never spoke much of

her Ellis Island experiences because she came as a 15-year-old girl, alone

with her younger brother. They were detained at Ellis Island for a week

because there was a question about their sponsorship. They had to stay

while they wrote for a letter to be sent to relatives and to receive the

reply, guaranteeing that they had financial backing and would not become

wards of the state. The girl remembered an overweight matron with a tattered

apron, with a huge ring of keys, who showed them to sleeping facilities.

Mom also mentioned Gus Wrage, a Gladbrook friend, who was one of twins

born on Ellis Island.)

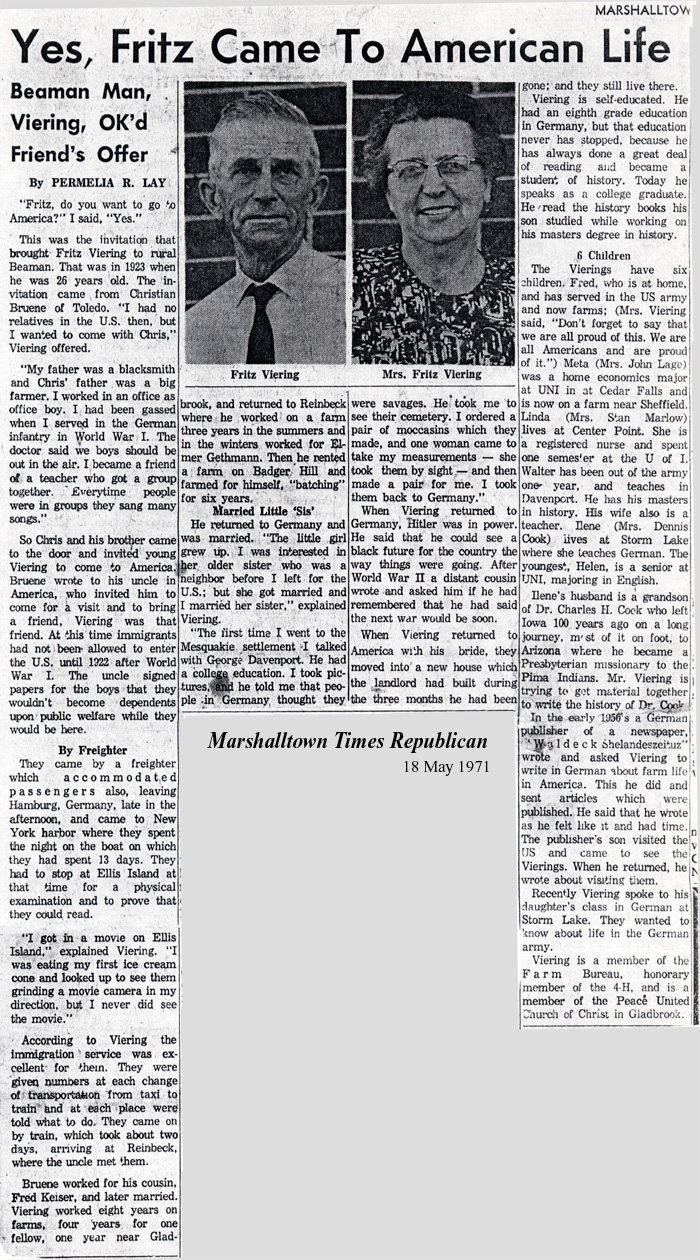

I read two

newspaper articles about speeches my father made to American Legion

meetings in the 1930s. I was amazed at the warm reception given to a former

enemy by veterans of the same conflict. When Dad spoke to the group, another

guest, Clarence Irwin—a Canadian architect—was in the audience

and soon realized that on a number of occasions, he and Fritz were directly

opposing each other, with some fierce fighting taking place. A few days

later a reporter from the Waterloo Courier arrived with Mr. Irwin

and for the next eight hours the journalist listened to the two former

“enemies” engage in an exchange of experiences that impressed

him. As the reporter later wrote to Dad, “One can read volumes and

volumes on the war and still not be informed as clearly nor as vividly

as hearing it firsthand from two [who] were in some of the stormiest battles”.

Those two opposing soldiers

became very good friends and shared letters and visits over a long period

of time. They continued their correspondence through the Great Depression

of the ‘30s and experienced times of great difficulty during those

years as well. The times were so distressing that Irwin wrote in a Christmas

card to Fritz in December of 1931, “Have been hoping to see you

for months, but no doubt you know some of the general hell going on as

well as we do. Honestly, Fritz, I have several times dreamed of the happy,

carefree days when you and I were hired to kill each other and wished

that I were as free from worry as I was then”. (Dad’s home

village of Kuelte, with 700 inhabitants, furnished about 200 soldiers

to serve in WWII; 45 or 50 never came back. Others were crippled or maimed

for life.)

Those first few years in America were lonely

and difficult for Dad. A hired man earned $60.00 a month and he was not

paid in the winter. He originally planned to return to Germany in two

years, as soon as he had saved enough money and paid off his sponsorship.

Mom’s theory was that one of the women on one of the farms where

he worked never gave him enough to eat. Not giving anyone enough to eat

was a cardinal sin according to my mother. Whenever we would go visiting,

the whole family of eight almost always went along. Mom would always take

along food to the home we were visiting. Mom was always known for her

bounteous lunches. She was famous as a bread baker, once having me draw

a picture of how to mix up the whole wheat-rye Graham bread, which she

made twice weekly; she didn’t really use a recipe. Since she was

going into the hospital for surgery, she wanted to be sure that if she

didn’t survive, my father would always have his rye bread, or Schwarzbrot.

On the back of the handwritten recipe card were these few lines:

Your

loving ways bring out the sun

And

warm the hearts of everyone.

I know why she scribbled those words—because that’s what she

believed.

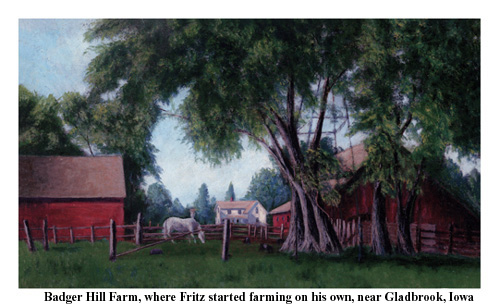

In March of 1934 Dad moved to the farm that he and his descendents would

rent for more than 70 years. The house was in terrible condition. I remember

Dad telling how cold it was in winter: the lace curtains at the leaking

windows would fly horizontally when the wind blew. He would sit in front

of the old wood cook stove with the oven door open, bundled in a coat.

“Wie Du”—his faithful Rat Terrier—would lie inside

the oven. Wie Du lived until he was 18 years old. His name was a German

phrase meaning “Like you”. The old house was in such a poor

condition that a new house was to be built to replace it. During the construction

period, winter of 1936-37, Fritz went

to Germany to visit family and friends. He also may have wanted to

find a bride. Several German women had corresponded with him during his

bachelor days in America, with matrimony the goal.

In March of 1934 Dad moved to the farm that he and his descendents would

rent for more than 70 years. The house was in terrible condition. I remember

Dad telling how cold it was in winter: the lace curtains at the leaking

windows would fly horizontally when the wind blew. He would sit in front

of the old wood cook stove with the oven door open, bundled in a coat.

“Wie Du”—his faithful Rat Terrier—would lie inside

the oven. Wie Du lived until he was 18 years old. His name was a German

phrase meaning “Like you”. The old house was in such a poor

condition that a new house was to be built to replace it. During the construction

period, winter of 1936-37, Fritz went

to Germany to visit family and friends. He also may have wanted to

find a bride. Several German women had corresponded with him during his

bachelor days in America, with matrimony the goal.

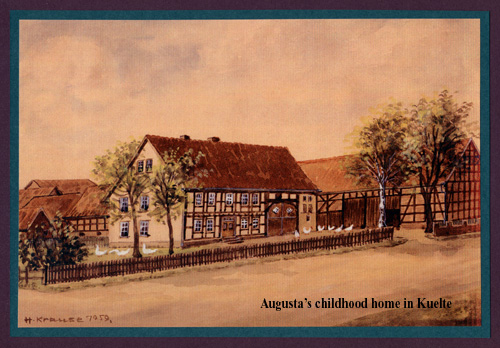

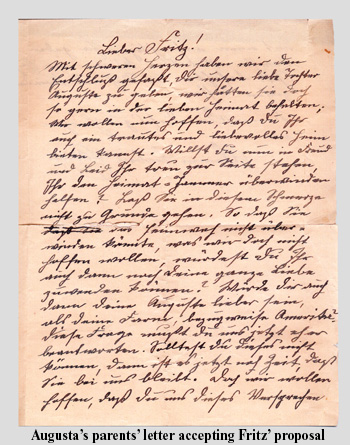

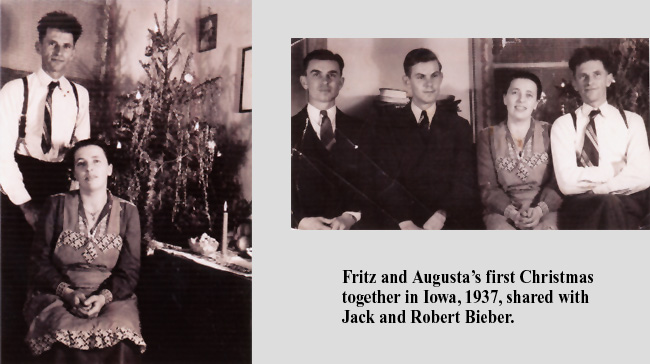

So begins the story of Fritz and Augusta’s marriage. The morning

that Fritz arrived in his home village of Kuelte, he walked down that

familiar street when he met my mother, Augusta (also born Viering), from

the house of Mangels, coming down the street. She was carrying a Stollen,

a Christmas fruit bread—mixed and shaped—to the bakery to

be baked. My mother said “Good morning”. They later met at

a dance. Mom told me that her father was home with the flu. If “Opa”

had been at the dance, Dad would not have been allowed to escort her home.

Fritz did ask Augusta, however, if he could walk her home. Mom said they

took the long way home. Dad said that at the dance he had noticed Mom’s

dark brown eyes. In February, Mom wrote a formal letter of acceptance

of Fritz’ proposal. Her parents wrote a letter to Fritz, too, expressing

their concerns, but they did grant their reluctant permission.

So begins the story of Fritz and Augusta’s marriage. The morning

that Fritz arrived in his home village of Kuelte, he walked down that

familiar street when he met my mother, Augusta (also born Viering), from

the house of Mangels, coming down the street. She was carrying a Stollen,

a Christmas fruit bread—mixed and shaped—to the bakery to

be baked. My mother said “Good morning”. They later met at

a dance. Mom told me that her father was home with the flu. If “Opa”

had been at the dance, Dad would not have been allowed to escort her home.

Fritz did ask Augusta, however, if he could walk her home. Mom said they

took the long way home. Dad said that at the dance he had noticed Mom’s

dark brown eyes. In February, Mom wrote a formal letter of acceptance

of Fritz’ proposal. Her parents wrote a letter to Fritz, too, expressing

their concerns, but they did grant their reluctant permission.

|

|

click here for documents

from Fritz

and Augusta's courtship and marriage

|

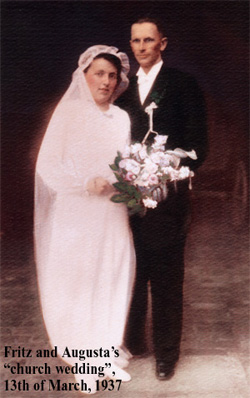

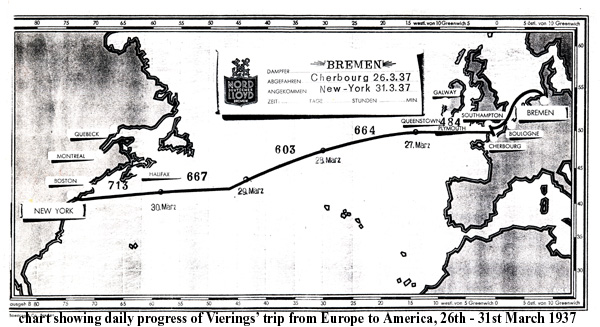

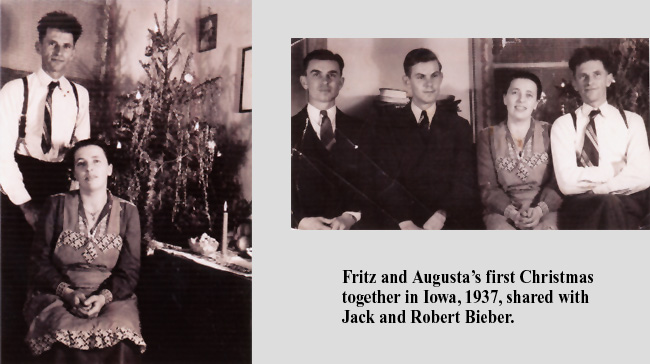

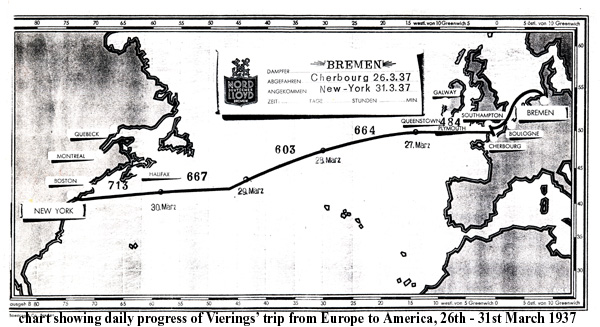

Following a whirlwind

courtship of less than three months, Augusta borrowed her sister Mariechen’s

white wedding dress for the church wedding. Ironically, Fritz had dated

this sister before he first went to America. The 12-year absence had been

just too long: Mariechen married someone else about six months before

Fritz returned to Germany! Augusta and Fritz’ wedding rings could

not be real gold because, Mom said, Hitler was not letting gold out of

Germany. (In checking Mom’s passport, it was called to my attention

that her status was as a “stateless person”: because she was

emigrating, her German citizenship was taken away.) The suit Dad purchased

in Germany for the wedding was partly made from wood fibers and it fell

apart soon after the wedding.

There was always one thing that Mom and

Dad could never agree on. And, that was the date of their marriage. They

were married by civil authorities on the 5th of March 1937. The church

wedding was to take place the next day, but Dad got sick and the church

wedding was postponed until the 13th of March 1937. Dad always said the

official wedding date was the day of the civil wedding; Mom, however,

said that the date of the church wedding was the day recognized by God.

When Mom went back to visit for the first time in 1953, she evidently

went both to the church and also the government office to get official

documentation of both events.

When Mom was recuperating from knee replacement

surgery, a niece, Micky, and I stayed with her for a few days. I had gotten

a Grandmother Remembers book to record special memories of her life. We

recorded some of her memories of their courtship and her growing-up years.

Augusta always said it was the saddest wedding she had ever been to because

they were sailing to a new country and her mother thought that she was

sending her daughter to the Wild West, with marauding Indians running

about. “Oma” was certain that she would see Augusta never

again, although Fritz and Augusta had promised that they would come back

for a visit in five years. That was not to be because when the five years

had passed World War II was raging.

The last words that my father told their

families as the train was leaving the station were “Come well through

the next war”. He believed that Germany was heading to war again.

Their German families did not believe that war would come [as most Germans

held that “Hitler wants peace; other countries are working to weaken

Germany]. When the war did come, by the time it was over, my grandparents

learned that two more grandchildren had been born during the years they

were not able to communicate with Fritz and Augusta on the faraway Iowa

prairies.

|

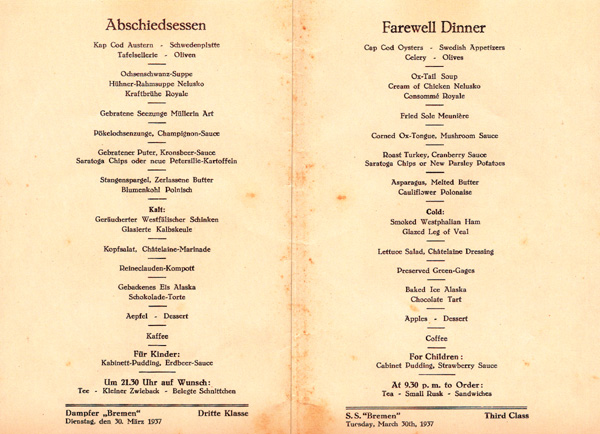

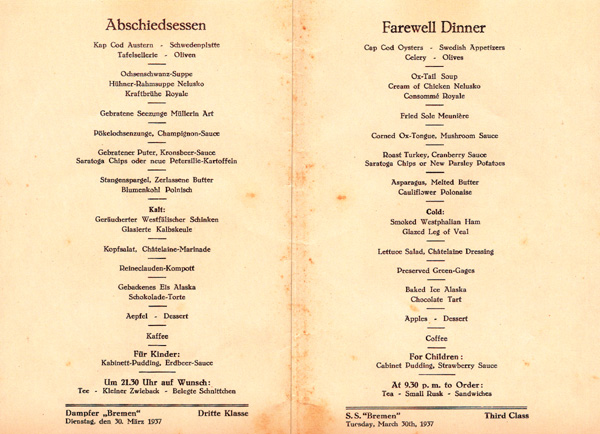

The Farewell Dinner menu aboard the

S. S. Bremen

on the 30th of March 1937 featured delicacies listed in both German

and English. This was the fare for third-class passengers. The menu

cover is shown to the left, the two listings inside the menu are

below.

Aboard the ship were many European refugees fleeing the Nazi madness—Jews,

political dissidents, artists, intellectuals and other so-called

"enemies of the German people". The various groups did

not necessarily like each other nor mix freely with one another.

All were trying to escape the gathering storm, any way they could. |

We never had much money, but we always considered

our lives very rich in a love of learning and caring. Four of the six

children became teachers, and one a nurse. Fred, the oldest, loved the

land, like his father. We saw our parents send package after package after

WWII was over—to family, friends and sometimes to people they scarcely

knew. Coffee, tea, cocoa, shortening, candy and many other items were

wrapped in cloth and sewn shut to discourage pilfering. The cloth sometimes

was feed sacks—also used by the recipients to make clothing for

the German families’ children. Even the thread used in sewing the

packages was saved. Some people later told them their care packages saved

them from starvation. My cousin, Fritz Viering Goebels, told us when we

visited them in 1998, that when one of the packages came it would be like

Christmas. The family would wait until evening and all sat around the

dining room table to see what was in it. Once, the coffee beans and rice

packages broke apart in transit and they carefully picked out the coffee

from the rice, as nothing must be wasted.

Kuelte remembered those packages sent after

the war. When Mom and Dad went back to Germany in 1971, they were greeted

by the mayor, who made a speech and presented my parents with a book.

Dad said “At least several hundred townsfolk must have been at the

place”. The Gesangsverein, a community chorus, sang for

them and people thanked them for the packages that had been sent 25 years

earlier.

Dad kept a daily travel diary on the 1971

trip—his only return to his homeland after he brought his bride

to America; Mom was able to return a number of times. Dad noted everyone

they visited each day and sometimes made a comment on their discussions.

One entry read “discussed WWI”. Another recorded “After

a very spirited visit all afternoon and evening…” My father

had many “spirited” visits, discussions or arguments all his

life. I remember growing up listening to these debates and found them

wonderful Sunday afternoon entertainment.

(Fritz’ relived his WWI experiences

in his mind during the last days, when his Alzheimer’s caused him

periodically to walk the corridors of the Westbrook Acres Care Center.

He touched the handrails all the while. He once told me that he was chasing

the rats. Were the rants from those long-ago WWI trenches? A sister also

said that Dad told her that as a boy the village of Kuelte installed a

sewer system—and that rats were everywhere. In some of the caretaking

training that our family attended, we learned that if a person has had

a traumatic experience in their early years, an Alzheimer’s patient

may relive them in their dementia.)

We loved and respected our father, but

he also was autocratic and opinionated, and when we were younger, we were

a bit afraid of him. We certainly didn’t ever want to disappoint

him. I remember there was one whistle for the dog, Wie Du and his successors,

and another for the children. We knew we were to come running when we

heard our whistle.

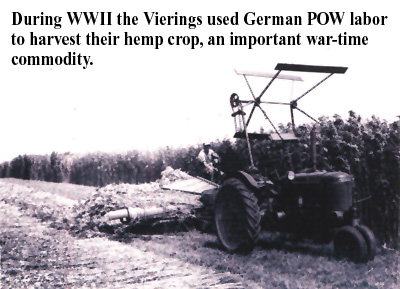

The Viering family has rented the same

120-acre farm since 1934, almost 70 years. The Great Depression devastated

so many. It was no different for the Vierings. We always had plenty to

eat, but had difficulty paying the cash rent during the Depression. It

took my parents ten years to catch up on the rent debt accrued during

those years. If Georg Keiser had not been so patient about the rent, Brian

Lage, a grandson, would not still be farming those Beaman acres. In later

years Mom and Dad were able to purchase a 240-acre farm near Gladbrook.

It happened to be one of the farms where Dad had worked as a hired man

during those first years in the United States. What an accomplishment,

to be able to purchase his own land! To be able to attain such a large

piece of the rich, black spoil of Iowa gave him such a sense of the fulfillment

of a long-held dream.

Dad also had the same feeling of accomplishment in being able to provide

a college education for five of his six children. My father had valued

education very highly. He could not afford to go to school more than to

the eighth grade in Germany. He was bitterly disappointed that his family

could not afford to continue his education in Germany. He was self-taught,

however, and could speak with authority with my professors at Iowa State

Teachers College [in Cedar Falls]. He also had written a letter to the

editor of the Saturday Evening Post and wrote for some German

publications. We didn’t realize how much he had written until we

were going through my parents’ home and found copies of many of

the articles he had written over a period of years. He was well-read,

reading late into the night after working long hours in the fields. It

was never too hot for him, although in the winter weather he often suffered

from the cold—a remnant of those war years. He loved Zane Grey,

stories of the west and the artist Norman Rockwell. A number of winters

he worked on a ranch in the Badlands area for a farmer who also had land

in Iowa.

Dad also had the same feeling of accomplishment in being able to provide

a college education for five of his six children. My father had valued

education very highly. He could not afford to go to school more than to

the eighth grade in Germany. He was bitterly disappointed that his family

could not afford to continue his education in Germany. He was self-taught,

however, and could speak with authority with my professors at Iowa State

Teachers College [in Cedar Falls]. He also had written a letter to the

editor of the Saturday Evening Post and wrote for some German

publications. We didn’t realize how much he had written until we

were going through my parents’ home and found copies of many of

the articles he had written over a period of years. He was well-read,

reading late into the night after working long hours in the fields. It

was never too hot for him, although in the winter weather he often suffered

from the cold—a remnant of those war years. He loved Zane Grey,

stories of the west and the artist Norman Rockwell. A number of winters

he worked on a ranch in the Badlands area for a farmer who also had land

in Iowa.

When Mom and my brothers and sisters gathered

around in the Stuba (German for “living room”) after

Dad’s death, everyone shared their own personal memories of our

father. I suddenly realized that one of his great gifts to us (after making

it possible for us to grow up as Americans) was that he made each one

of his children secretly believe that we were his favorite.

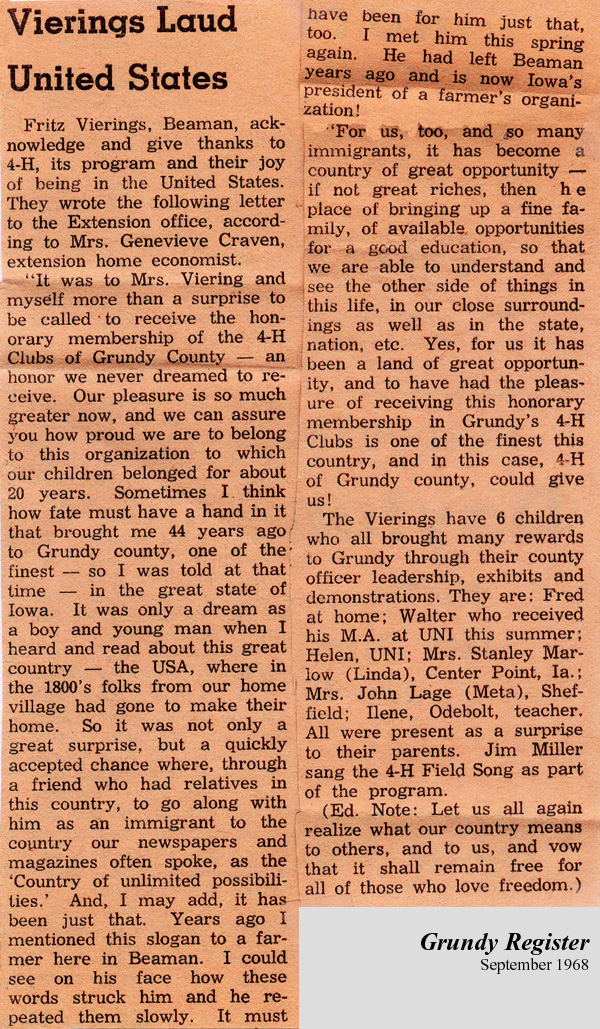

My father took pride in being an American

and he taught us to be proud and responsible citizens. He also taught

us to be proud of our German heritage. He told it best in his own words.

In a 1931 Traer Star Clipper article, Dad said “When I

came to America I planned to return to Germany in two years. It is now

nearly eight years since I came and I haven’t been back yet. I know

now that I will never go back except for a visit. I want to go back some

day to see my home, folks and former buddies of the war, and I’d

like to see the old battlefields again. But for nearly three years now

I’ve been an American citizen. America has been good to me. Once

I swore allegiance to the Kaiser [the German emperor, defeated in 1918,

at the end of World War I], and I did my duty to my fatherland as I saw

it them. Since then I have sworn allegiance to America and I hope to be

a good citizen of my adopted country”.

| Home |

|

Dad also had the same feeling of accomplishment in being able to provide

a college education for five of his six children. My father had valued

education very highly. He could not afford to go to school more than to

the eighth grade in Germany. He was bitterly disappointed that his family

could not afford to continue his education in Germany. He was self-taught,

however, and could speak with authority with my professors at Iowa State

Teachers College [in Cedar Falls]. He also had written a letter to the

editor of the Saturday Evening Post and wrote for some German

publications. We didn’t realize how much he had written until we

were going through my parents’ home and found copies of many of

the articles he had written over a period of years. He was well-read,

reading late into the night after working long hours in the fields. It

was never too hot for him, although in the winter weather he often suffered

from the cold—a remnant of those war years. He loved Zane Grey,

stories of the west and the artist Norman Rockwell. A number of winters

he worked on a ranch in the Badlands area for a farmer who also had land

in Iowa.

Dad also had the same feeling of accomplishment in being able to provide

a college education for five of his six children. My father had valued

education very highly. He could not afford to go to school more than to

the eighth grade in Germany. He was bitterly disappointed that his family

could not afford to continue his education in Germany. He was self-taught,

however, and could speak with authority with my professors at Iowa State

Teachers College [in Cedar Falls]. He also had written a letter to the

editor of the Saturday Evening Post and wrote for some German

publications. We didn’t realize how much he had written until we

were going through my parents’ home and found copies of many of

the articles he had written over a period of years. He was well-read,

reading late into the night after working long hours in the fields. It

was never too hot for him, although in the winter weather he often suffered

from the cold—a remnant of those war years. He loved Zane Grey,

stories of the west and the artist Norman Rockwell. A number of winters

he worked on a ranch in the Badlands area for a farmer who also had land

in Iowa.