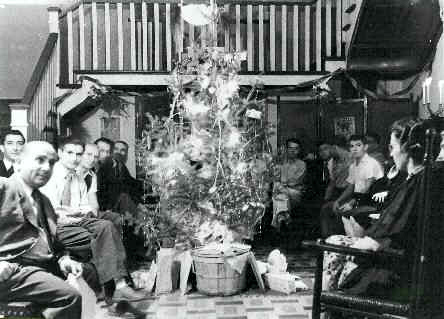

Quaker

Hill, 1940-41 Quaker

Hill, 1940-41

Although modeled on the hostel at Scattergood, the Friends-operated refugee

center at Quaker Hill differed in key ways from the prototype upon which it

was based. Sheltered in a large, white-pillared house donated by a wealthy

Quaker manufacturer, the hostel was located in Richmond, Indiana--a Midwest

town of 33,000 with a large Quaker heritage and population, as well as home

to Earlham, a small Friends college. Much more so than rural Iowa, Richmond

suggested the milieu typical of the industrialized, relatively densely

populated Lower Midwest stretching from the Mississippi to the headwaters of

the Ohio. There, American Friends Service Committee [AFSC] and volunteer staff who organized Quaker Hill hoped to

more easily and fully integrate that project into its surrounding community.

Undertaken at the urgent request of Jewish organizations and

others working with refugees, Quaker Hill operated on the assumption that a

group of people unknown to each other before might learn to live together

and work

cooperatively

in peace and harmony. The housekeeping, care of the grounds and buildings

are shared by all. In addition, all members of the group contributed three

hours of work daily-hard physical work-to the hostel. Thus, a sound

balance between mental and physical activity was sought.<1>

In contrast to the site on the wind-swept Iowa prairies, in the rolling

South-Indiana woods AFSC hoped to place more refugees directly into

industrial positions. Located almost equidistant between Cincinnati and

Indianapolis, Richmond's 55 manufacturing facilities employed some 4,000

people and produced a diverse assortment of lawn mowers, school bus bodies,

metal castings, caskets, farm implements, etc. While occupation retraining

per se was not offered, the philanthropist who had given the hostel site to

AFSC also made provisions for some of the refugees to work at an adjoining

four-story oil mill for refugees with business experience

around whom

could be developed one or more small business enterprises, which would

employ other refugees [or facilitate] some project like putting together

pre-fabricated houses...in connection with the city of Richmond and also

the U.S. Government.<2>

Quaker Hill's overseers intended not just the mill to be a vehicle for default

occupational therapy, but--like at Scattergood--that the reconstruction of the

site<3> itself would offer an

opportunity

for the work element found to be desirable in the daily program of [a]

Refugee Hostel, as well as the [focus of a] program of the Peace Camp and

similar activities for young Friends. A competent foreman [was] secured to

direct this work of reconditioning who [could] use tactfully and helpfully

the service of these people.<4>

The work

component of Quaker Hill, however, often ran better than the educational one

at the hostel. Mary Lane Charles--who had volunteered at Scattergood until

she transferred to Quaker Hill--reported the Richmond site had endeavored to

"fulfill the refugees' need for English in as large a variety of ways

as possible". The backbone of the program had been individual tutoring

and classes, but the "chief demand" remained that of instruction

in English grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation. Although the mostly young

Quaker volunteers at the hostel frequently offered subjects such

as American history, sociology or geography, Charles reported: "our

efforts met with little response, except for a class in American literature,

given once a week by a teacher from Richmond". During most of the year

the staff held two classes daily-one for those with "slight knowledge

of English" and one for advanced pupils. Twice a week students from

Earlham College's Speech Department visited to give individual phonetics

lessons. In addition, refugees were entitled to an hour's tutoring a day if

so desired and "most of the residents took advantage of this

opportunity". The staff even organized a special table for beginners presided over by one of the Civilian Public Service

volunteers at Quaker Hill. Various staff shared the responsibility for being

available

for

conversation in the parlor in the evenings. During several months short

current events talks were given after dinner by residents and occasionally

by staff-members. This was finally given up on the request of the

residents, as many of them were distressed at having to dwell on war news.<5>

The hostel did sponsor a series of panel discussions focused on

"subjects of current interest", such as "Economic Causes of

the Present War" or a review of "American and European

Etiquette". Frequent public-speaking appearances and the writing of

articles for local newspapers gave refugees practice in using English skills

they were developing at Quaker Hill. Staff encouraged residents to attend

lectures or other programs both at Earlham College and at Quaker Hill

itself. The hostel held over 30 lectures, often "by someone from

Richmond" on aspects American life such as the educational system,

journalism in the U.S. or "illustrated travel talks on some region of

America". At other times visiting Friends talked about Quaker relief or

reform work and gave news of conditions in Europe. In a more informal mode,

the staff also hosted teas to which Richmondites were invited--

most of

which included a talk by an American guest, usually an Earlham professor,

on subjects such as Quakerism, American music, etc... Richmond friends

cooperated generously in inviting residents to their homes for tea or

dinner and introducing them to other Americans of similar interests.<6>

If it were not perfect, Quaker Hill's program at least earned praise at

least from the New York German-language Jewish newspaper, Der

Aufbau, which claimed that refugees who had found a haven at

Quaker Hill could

plan in

peace and safety, under experienced leadership, a new life... Reinforced

in soul and body with new confidence in the future, these new Americans

have found a new field of working.<7>

The Aufbau's

claim was not exaggerated, as examples of refugee placements secured through

Quaker Hill abound. To list a few: doctor Alex Szittya became a resident

physician at a general hospital in Chester, Pennsylvania. Johann Suskind

located a sales job and drove a delivery van in Indianapolis. Friedrich

Schweiger was appointed foreman at company in Evansville, Illinois--while

Franz Foges also found employment in that Chicago suburb. Walter Ellinger

landed a job at a Cincinnati cookie factory and Gus Ferl a job in

Indianapolis. In a less laborious vein, Norbert Silbiger had "a very

successful year" directing plays at Richmond's Civic Theater and

Earlham College.<8>

Quaker Hill operated from July 1940 till September 1941, at which point it

closed "due to immigration restrictions". As its own last report

assessed, the hostel had given the 55 refugees--"victims of Europe's

terror"--who sojourned there during that time "a chance to find

themselves, and to become adjusted and ready for American life and

citizenship".<9>

Quaker

Refugee Projects:

Agricultural

Projects | Boarding Schools | Rest

Homes | Hostels

Footnotes

|

<1>

|

Undated, unsigned broadsheet, "Quaker Hill as a Hostel for

Refugees".

|

|

<2>

|

Isaac Woodward, Letter to John Rich, 20.XI.40.

|

|

<3>

|

The site consisted of the main house, a shop, a new CPS-built frame

dormitory and an assembly building, situation on 25 acres "of

beautiful grounds and gardens [which] add to its charm and

usefulness" (Isaac Woodward and Millard Markle, Report titled

"Quaker Hill: A Friends Service Center", 1.I.42 .

|

|

<4>

|

Murry Kenworthy and Frances Doan Streightoff, Report titled

"Meeting of the Friends Peace Camp Project, held at Richmond,

Ind., March 14, 1940".

|

|

<5>

|

Mary Lane Charles, Undated report titled "The Educational

Program at Quaker Hill".

|

|

<6>

|

Ibid.

|

|

<7>

|

"Quaker Hostels", a previously translated article from

Der Aufbau, 21.II.41.

|

|

<8>

|

Quaker Hill's monthly newsletter, The Quaker Hill Post, August

1942.

|

|

<9>

|

Isaac Woodward and Millard Markle, Report titled "Quaker Hill:

A Friends Service Center", 1.I.42.

|

|

| | | | | | | |

| Home |

|