| Home |

German POWs' articles about Camp Algona

Slide show presentation about Camp Algona by Michael Luick-Thrams

Slide show presentation about Camp Algona by Steve Feller

The LegacyBy the end of the Second World War some 400,000 German Italian and Japanese POWs found themselves imprisoned in the United States; millions more Axis and Allied POWs were held in camps in Europe, the Soviet Union, Canada, Australia and Africa. While Axis POWs were both the perpetrators as well as victims of dictatorships and state terror, both sides⠐OW experiences embody ageless, timely themes of war and peace, justice under arms and issues regarding human rights, international reconciliation and future conflict avoidance.

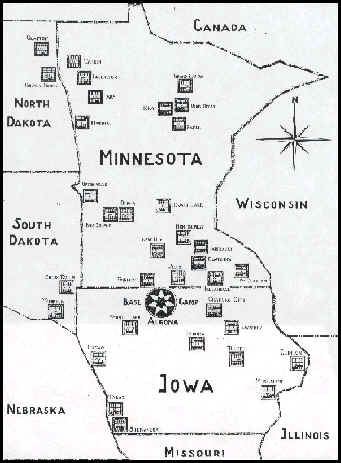

From 1943-46 Camp Algona in Iowa and itⳠ34 branch camps in Iowa, Minnesota and both Dakotas housed up to 10,000 German POWs. [Iowa was one of only a few states to see POWs from all three Axis nations: itⳠfirst POW base camp, Camp Clarinda, housed initially German, then Japanese prisoners; Italian POWs built Camp Algona before German ones full occupied it.] As TRACES⠥xecutive director and a native Iowan at home in Berlin and in Iowa, historian Michael Luick攨rams has preserved myriad stories of German POWs imprisoned in the Camp Algona system. The RelevanceThe stories of German POWs in Iowa确d as a comparison, those of Iowa POWs in the Third Reich紲anscend clich鳍 and polemics: they challenge those who encountered them to deal with the origins and the effects of dictatorships and militarism, with war as a 㴯ol䠯f statecraft and with the larger legacy of WWII. And 砡s a case study 砩n an era of demanded German compensations for forced labor, learning German POWs⠳tories reveals that the majority were returned to Europe early in 1946碵t rather then to their own country, to work in Britain or France until as late as fall 1948. [A third of the 3.5 million German POWs sent to Siberia at the warⳠend literally were worked to death, those who did return to Germany trickled back as late as 1956.] The question arises: what indelible human rights do capture enemy soldiers retain, regardless of all other considerations?

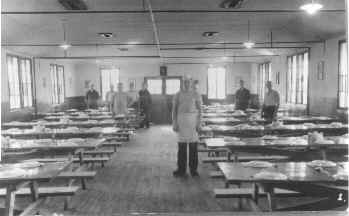

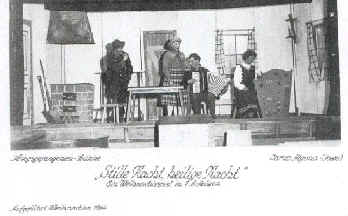

Conversely, the Third ReichⳠalmost exclusively ungenerous, heavy-handed and often arbitrary treatment of U.S. POW筯re of whom came from Iowa, per capita and in raw numbers, the any other state秥nerated ill will of at least indifference regarding GermanyⳠpost-war fate and spoiled most of an entire generationⳠability to respond to German culture or people in rational, sympathetic or welcoming ways. While it is not TRACES⠧oal to 㲥buke䍊 Germans alive today, we believe that both Americans and Germans can benefit from critically examining this shared past. To facilitate that process we have gathered, preserved and now present碥fore they are lost to the world糴ories of German an Iowa POWs as they were imprisoned on each others⠳oil during WWII. By doing s, we hope that todayⳠand future generations might understand and emulate the qualities of the universal human sprit that allow us to rise above and eventually defeat the prejudices, fears and conflicts which otherwise can demean and destroy us. The ProjectAlthough POWs have been the focus of a number of academic works and popular films, TRACES⠭ain goals are education and increased awareness, not just research or entertainment; ours is an effort to raise universal issues such as personal accountability and civic responsibility, the fluid lines between 㧯od⠡nd 㥶il䬍 revenge and compassion, 㰥rpetrators: and 㶩ctims䗴he inalienable humanity of both. To create foci for exploring those issues, in the summers of 2001 and 2002 a TRACES research team filmed over 75 hours of interviews with former German and Iowa POWs or their family members. It also collected many artifacts related to the former German POWs: over 300 hundred photos, contemporary films of Camp Algona and POWs at work on Minnesota farms, more then 250 letters between the upper Midwest and Germany during and after the war, numerous POWs journals, religious or text or other books, camp 㭯ney䬠hand made maps, numerous paintings and cartoons and sketches, chess pieces carved from stolen army broomsticks, certificates and Ids, U.S. Military checks payable to Europe-bound POWs, a pipe and a toiletry bag brought in camp canteen, razor and paint sets, wood carving tool, four duffel bags, sheet music, memoirs, the POW-crafted 2/3rds-life-size nativity scene, etc.

A "tour" of the German POWs' daily-life world follows:

|

||||||||||||||

Encounters between Midwesterners and German or Austrian POWs

Bob Baker | Bill

Berg | Jim Fitzgerald

| Evelyn Grabow | Byron

Holcomb

POWs in America | POWs in the South |Italian POWs | German POW "Re-education" |

Those German and Italian POWs held in over 500

camps across the U.S. were sent out to harvest and process crops, build

roads and waterways, fell trees, roof barns, etc. In the process, they

formed significant, often decades long friendships with 㴨e enemy䍊 and under went considerable changes as individuals and as a group紨us

fundamentally influencing post-war German values and institutions, as

well as American-German relations. Many even emigrated to the U.S. after

the war.

Those German and Italian POWs held in over 500

camps across the U.S. were sent out to harvest and process crops, build

roads and waterways, fell trees, roof barns, etc. In the process, they

formed significant, often decades long friendships with 㴨e enemy䍊 and under went considerable changes as individuals and as a group紨us

fundamentally influencing post-war German values and institutions, as

well as American-German relations. Many even emigrated to the U.S. after

the war. Further, by bringing Axis POWs to the U.S., the

Allies inadvertently defanged even the most ardent Nazi POWS and created

㌩ttle Ambassadors䮠First, Nazi loyalists among the Germans saw

that the wild and rabid anti-U.S. propaganda that they had been fed

didnⴠfit what they saw in America. Second, all German POWs learned

by example what democracy looked like on a daily, personal basis. Third,

after the German capitulation some were chosen for special

㲥-education䠴o counter lingering post-war Nazi ideology once

backs in Europe. Fourth, most German POWs took with them to Germany news

and views of America which, by and large, spoke well of the U.S.紨e

land of their victors and former 㥮emies䮼/span>

Further, by bringing Axis POWs to the U.S., the

Allies inadvertently defanged even the most ardent Nazi POWS and created

㌩ttle Ambassadors䮠First, Nazi loyalists among the Germans saw

that the wild and rabid anti-U.S. propaganda that they had been fed

didnⴠfit what they saw in America. Second, all German POWs learned

by example what democracy looked like on a daily, personal basis. Third,

after the German capitulation some were chosen for special

㲥-education䠴o counter lingering post-war Nazi ideology once

backs in Europe. Fourth, most German POWs took with them to Germany news

and views of America which, by and large, spoke well of the U.S.紨e

land of their victors and former 㥮emies䮼/span> In total, the narratives and artifacts document a

story, which takes turns unexpected of former participants in such a

deadly war machine as the Third ReichⳠWehrmacht. Without exception,

each of the German POWs interviewed issued moving statements against war

and for peace确d that the theme appears repeatedly in their accounts,

intimately illustrated with personal, vivid details. As these veterans

were both the perpetrators and the victims of Nazism, theirs are

uniquely rich as modern 㷡r tales䮼/span>

In total, the narratives and artifacts document a

story, which takes turns unexpected of former participants in such a

deadly war machine as the Third ReichⳠWehrmacht. Without exception,

each of the German POWs interviewed issued moving statements against war

and for peace确d that the theme appears repeatedly in their accounts,

intimately illustrated with personal, vivid details. As these veterans

were both the perpetrators and the victims of Nazism, theirs are

uniquely rich as modern 㷡r tales䮼/span>